Bitcoin: Life After 21 Million

Ever since the 17 millionth Bitcoin was mined just over a week ago, we are one step closer to the inevitable day when there will no longer be any Bitcoins left to be created. Although the final Bitcoin will not […]

Ever since the 17 millionth Bitcoin was mined just over a week ago, we are one step closer to the inevitable day when there will no longer be any Bitcoins left to be created. Although the final Bitcoin will not be mined until May 2140, most of the Bitcoins will have been depleted way before that – sometime before 2030, we would have crossed the 20 million Bitcoin mark. This means that the last 1 million Bitcoins will take over a century to mine.

Source: The Saif House

The exponentially decreasing amount of Bitcoins minted in the form of block rewards does not bode well for Bitcoin miners. Since the vast majority of miner revenues come from block rewards, the decreasing nature of their source of income through a process known as the ‘halvening’ means that the amount of block reward will eventually dwindle to a certain level that Bitcoin mining will no longer be profitable. As a result, the source of the miners’ income will eventually depend on transaction fees, which will bring about various repercussions regarding the security and the stability of the coin.

Here are three possible scenarios that might arise when block rewards become obsolete:

Profitable Forking

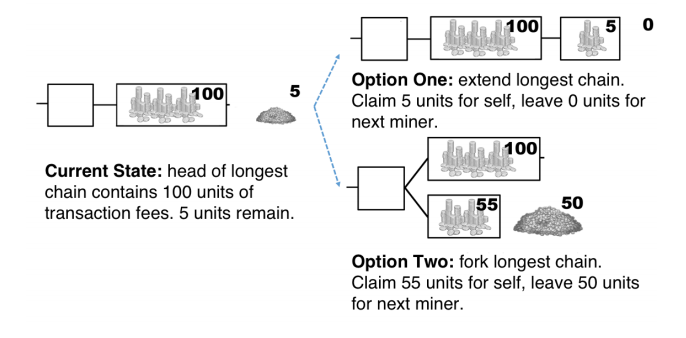

When the miners’ reward depend solely on transaction fees, the variance of the miner reward is very high due to the randomness of the block arrival time. Thus, it becomes much more lucrative for a miner to fork a “wealthy” block to “steal” the rewards therein.

Source: Freedom to Tinker

To put this into perspective, imagine a group of rational, self-serving miners faced with a blockchain of blocks. Now that there are no longer fixed block rewards, each of those blocks will contain varying amounts of rewards that come from transactions of different sizes. Here, the miners can choose to either extend the longest head of the longest chain (AKA the block that has the most rewards), procuring a reward of 5 arbitrary units and leaving behind no rewards for the next miner, or she could fork the block, obtaining a reward of 55 units and leaving behind 50 units for the next miner.

It is obvious that the second option is more profitable for the miner, but according to the Bitcoin protocol, the miner should have gone with the first option. Therefore, without a fixed block reward, mining activity is no longer analytically tractable, not to mention the non-uniform rate in which transaction fees arrive, which complicates things even more. This makes predicting mining behavior to be incredibly complex in the near future.

Undercutting

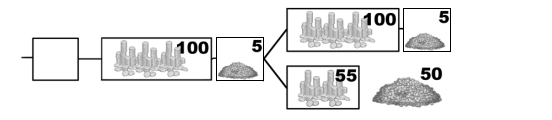

As a result of profitable forking, comes the risk of undercutting attacks, where miners “actively fork the head of the chain and leave transactions unclaimed in the hope of incentivizing PettyCompliant miners to build on their block” (SOURCE). To understand what PettyCompliant is, we will have to revisit the idea of profitable forking.

Source: Freedom to Tinker, modified.

Whenever a profitable fork takes place, the remaining group of miners are faced with a 1-block fork and the dilemma of which block they should keep mining next. In that case, it will be more profitable for the next miner to build upon the block that leaves the most available transaction fees rather than the oldest-seen block. In the example above, it will be the second block – the block that was conceived by the profitable fork. This strategy is known as PettyCompliant.

Selfish Mining

According to the Bitcoin protocol, Bitcoin mining can only work when a majority of the miners are honest; that is, follow the Bitcoin protocol as prescribed (Eyal & Sirer). However, there is a strategy that could be used by a minority pool to obtain more revenue than the pool’s fair share. This strategy is known as ‘selfish mining’, and it allows miners to achieve more than its ratio of the total mining power of a mining pool.

When transaction fees substitute block rewards as the main incentive for miners, selfish mining is predicted to run rampant because of this line of reasoning: if a miner happens to mine a new block just seconds after the last one was discovered, it wouldn’t make sense for them to publish it right away since they will not be gaining anything. Thus, the miner will choose to keep its discovered blocks private, thereby intentionally forking the chain in hopes to form a private branch.

While the other honest miners continue to mine on the public chain, the selfish miner will keep mining on its own private forked branch. Therefore, whenever the selfish miner discovers more blocks, it develops a longer lead on the public chain because of the blocks that it kept private from before. Eventually, when the length of the public branch matches that of the selfish miner’s private branch, the selfish miner will then reveal blocks from their private chain to the public.

This withholding of mined blocks hampers the integrity of the blockchain and makes it vulnerable to double-spending attacks. All this is due to the variance in transaction fees – when there is a fixed block reward in place, it wouldn’t make sense for the aforementioned strategies to be practiced amongst miners in a mining pool.

How This Impacts Bitcoin’s Security

Any of these anomalous strategies, if to be implemented, will have serious repercussions on Bitcoin’s blockchain infrastructure. Due to the recurring forks, there will be a significant portion of “stale or orphaned blocks” on the blockchain, making it more vulnerable to more than half of the attacks launched at the blockchain, not to mention the increased transaction confirmation time.

Worse comes to worst, the pre-existing consensus of the blockchain will break down due to excessive block withholding or increasingly aggressive undercutting. Therefore, a fundamental reassessment of the role of block rewards in Nakamoto’s design of Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system is crucial to ensure Bitcoin’s survival in the long run.